A Discussion Of What Is Actually Driving The Rebound In U.S. Capital Markets

U.S. capital markets are seeing a rebound with ECM rebounding sharply and IG debt hits record highs fueled by Fed cuts, but a steepening yield curve driven by massive fiscal deficits signals underlying market strain and potential political volatility.

Analysing Investor Nervousness Around Big Tech

Investor nervousness is growing over Big Tech’s massive AI spending, with high valuations and soaring CapEx leading to a recent market sell-off. This article explores the rising debt levels, operating costs, and fundamental valuation concerns that are causing jitters from Wall Street to Asia.

Exploring the Role of Primaries as the Engine Room of Private Equity

Primary private equity is the quiet workhorse of institutional investing, systematically delivering 15-25% compounding returns. Discover why this long-duration asset class remains the essential backbone of a sophisticated portfolio, even as its structures evolve.

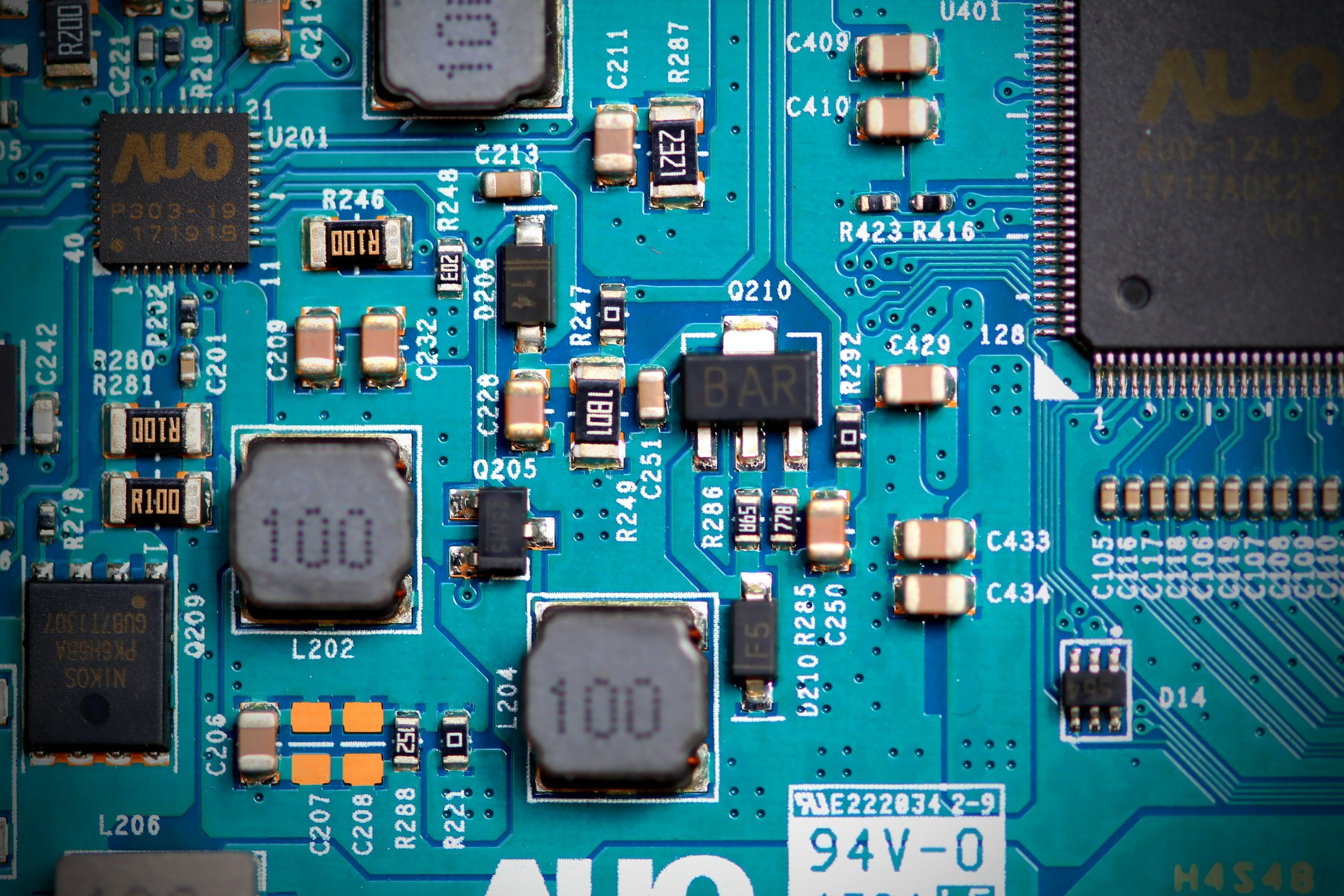

An Assessment of the Revival of US Semiconductor Manufacturing

The US is investing hundreds of billions to secure its chip supply chain for national security and AI, but this high-stakes push faces critical foreign dependencies, environmental trade-offs, and a severe talent shortage.

An Outlook On UK Equity Markets

The UK equity market has stayed quiet through most of 2025, though there are now visible signs of improvement as inflation cools and rates begin to fall.

An Analysis of European Infrastructure

European demand for infrastructure is growing with key drivers in the form of the green and digital transition, heightened geopolitical tensions, and the rapid rise of artificial intelligence. However, the continent faces a substantial investment gap, expected to reach US$2 trillion by 2040, which would require both public and private capital to address.

A Discussion on Private Credit

Private credit continues to surge as institutional investors seek alternatives to volatile public markets. With banks retreating from lending, direct lenders are stepping in to finance mid-market deals at record volumes and yields.